IMAGINATION AND PARTICIPATION: NEXT STEPS IN PUBLIC LIBRARY ARCHITECTURE

In December 2021, the English-language book ‘Imagination and Participation’, in which authors Rob Bruijnzeels and Joyce Sternheim give their vision of the future architecture of public libraries, was published by publisher nai010. Central to the book is the question of how public libraries can respond to changes in our society and what implications that has for the architecture of new library buildings

WHY THIS BOOK?

For a long time the opinion prevailed that library buildings would become superfluous due to further digitization of information. Nothing has turned out to be further from the truth. Visitor numbers continue to rise, making public libraries now among the most visited cultural institutions worldwide. This also grows the appreciation of the public library as a public space, those scarce places where people of all ages and from all walks of life can walk in, without the obligation to buy or consume anything.

A place where you can really meet the other, where people can pay attention to each other’s thoughts and actions and to the community of which they are a part.

The realization that such public space is essential to the social and cultural vitality of a community is leading to a true renaissance of library architecture. All over the world, impressive new libraries are springing up, often designed by famous architects. Because every city wants its own icon, a characteristic building that attracts a lot of public and thus also acts as a booster for area development. But do those buildings really represent a new vision of the public library’s role in society?

We sometimes see spectacular new libraries that, on closer inspection, are quite traditionally designed. The archetype of the library in ultra-modern packaging. In addition, we see flashy buildings, which accommodate a wide variety of activities, but which are hardly recognizable as libraries because the collection has been given a secondary role. These different interpretations are illustrative of the public library’s search for a new identity. A quest that has everything to do with the social changes that affect libraries at their core.

Public libraries face the massiveness and ubiquity of the Internet and social media, increasing inequality and polarization, and a decline in the sense of community. Complex issues that call for the next step in the development of the public library. The library’s classic distribution model, based on selecting, unlocking and making information available, is no longer adequate. The accessibility and availability of all kinds of resources is important, but even more important is the existence of meaningful connections between those resources. It is precisely by organizing this coherence that the public library can distinguish itself.

This involves not only presenting a collection or the interaction between users and collection, but also the interaction between users themselves and showing the results of that interaction. As a result, the public library’s innovation mission is much more comprehensive and complex than the application of new information technologies, but is primarily about reshaping processes aimed at encouraging and supporting active citizenship and participation. This irrevocably leads to the question of which building will make this new way of working possible: a building in which various forms of interaction are given shape, but in which the collection also still has a prominent, but different role.

Finding solutions to this architectural challenge requires not only imagination and knowledge of the essence of public library work, but also the expertise of architects and specialists in public space and cultural placemaking.

SIX THEMES

The richly illustrated book consists of six themes that are obviously interrelated, but readers can navigate through the book in their own way according to their interests.

TRANSITION: I HAVE TO CHANGE TO STAY THE SAME

With this quote, artist Willem de Kooning emphasized that he could only stay true to his passion if he constantly changed. This is equally true for public libraries. A future strategy can only be successful if the library remains true to its classic cultural and social value. But then what is “the change” and what is “the same”? In our view, in addition to personal development, the library must also focus on the development of the community as a whole. This means a shift in focus from lifelong learning to lifelong participation. It calls for a library that enables people – supported and inspired by the collection – to engage in conversation about social issues that affect both themselves and the local community.

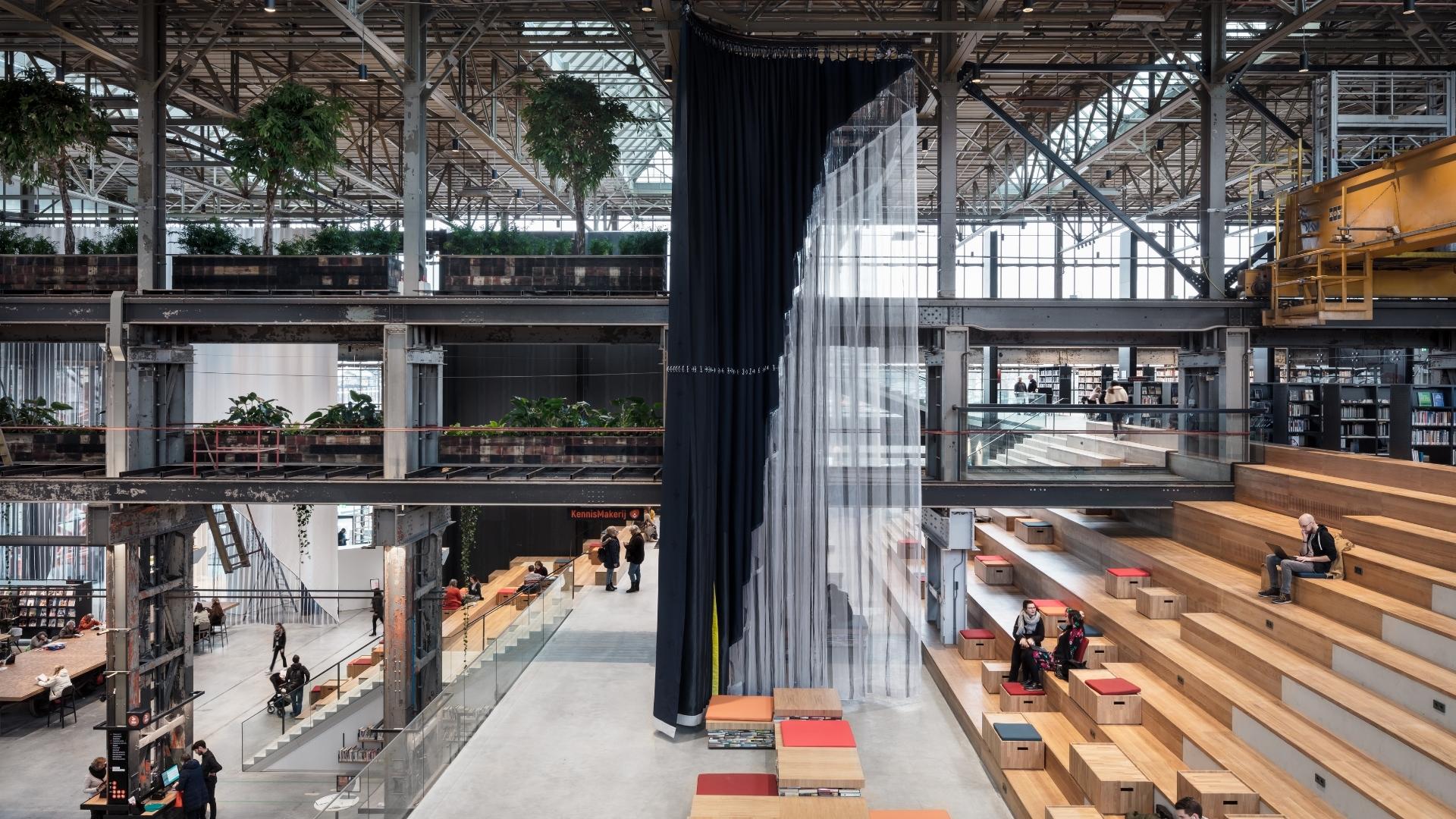

VALUES: CATHEDRALS OF THE MIND; HOSPITALS OF THE SOUL; THEME PARKS OF THE IMAGINATION

That public libraries play a unique role in society can be attributed to a number of distinctive qualities. Naming those qualities more explicitly helps to further clarify the library’s position in society and the urban environment. The library is a place for physical encounter and exchange between people of different backgrounds and opinions. A place where people feel free to engage in conversation and reach mutual understanding, while surrounded by sources of knowledge and information: the collection. But also a place where people get the idea that they can develop themselves and change the direction of their lives. Descriptions such as meeting place, Third Place, or living room do not adequately reflect the significance and complexity of what takes place in the library. A better description is heterotopia, which literally means “other place. It is the in-between space where you can develop and where your perspective can change through interaction with other people and other cultural expressions. Such a characterization obviously has implications for the architecture and layout of the building, but it also means that the library can claim a place of its own in the urban infrastructure. The Groninger Forum and the Tilburg LocHal make it clear how important it is to take the local context into account.

TYPOLOGIES: THERE IS NO ARCHITECTURAL FORM UNIQUE TO THE LIBRARY

Architects and art historians use typologies to discern common characteristics or principles for buildings. It is a way of looking systematically and with an objective eye at similarities or resemblances between buildings. Recognizing and using typologies can provide direction in the design process of a new library building. It allows us to “read” and peruse existing library buildings; it provides references and gets you thinking. Library buildings are constantly responding to change, such as the growing size of the collection, the introduction of new media, the ways in which those media are stored, loaned or secured, and the ways in which users can access and use those media. This is no longer about the appearance of a building – its stylistic features, the movement within which it fits or its immediate recognizability – but about how the library functions on the inside. Designing the public library of tomorrow has therefore become a challenging task. If librarian and architect are complementary partners in that process it can result in new, jointly developed typologies. A great challenge where the librarian becomes a bit of an architect. And vice versa. The best of both worlds!

PARTICIPATION: MAKING THE WORLD SAFE FOR QUESTIONS

For a long time, the primary process of libraries focused on passively making a good collection available. Collections were assembled with great care, and it was up to the users to choose from them according to their individual judgment. It is a model that revolves around accessibility and distribution of information. But that’s probably not good enough in times of information overload. We are faced with the choice: should we focus on improving the existing distribution process or do we focus all our attention on what is truly valuable; the library beyond the information overload.

The Ministry of Imagination developed a process, which focuses on knowledge creation and sharing. In doing so, the library looks for the knowledge, creativity and imagination present in the city. It is a process that begins with inspiration, with good questions, surprising and sometimes unusual collection presentations. Visitors are invited to respond: what are their own associations? What knowledge do they have to add and what new views will emerge? When the results are systematically shared with other visitors, new connections, new meanings, and new insights continually emerge. It is a new, cyclical process of inspiring, creating and participating.

Within this new library process, the collection plays a very different, activating role that goes far beyond a passive presentation to users. The collection is used first and foremost to invite people to delve into questions or themes. At that point, the collection is a source of knowledge and inspiration. If you invite users to explore their own perspectives and experiences, the collection acts as a working material for creating new meanings. Inspiration comes when those newly acquired contexts are added back to the collection. The collection is thus developing into a living archive, in which you can see what themes have been researched and what new knowledge and insights this has led to. The main premise here is that library users and collaborative partners can each contribute to the programming and the various components of the process from their own quality and expertise.

The construction or remodeling of a new library is a unique opportunity to apply these principles. To make all activities literally visible in the building, an open plan design is needed, in which functions are integrated as much as possible. In our designs we prefer to use the typology of a landscape that consists of a collection of diverse ‘biotopes’, which are connected to each other, but each has its own atmosphere and appearance: open and accessible, so that people see what is going on there and are more quickly tempted to participate. With spaces that enforce silence or, on the contrary, stimulate liveliness and social contact; spaces where you can enjoy art, music and literature and spaces that invite you to produce something yourself or display your talents. As an important source of knowledge and inspiration, the collection is omnipresent, and makerspaces – as places where work is done with the collection – also deserve an integrated placement as part of the public space.

INSPIRATION: CONVERSATIONS WITH ARCHITECTS

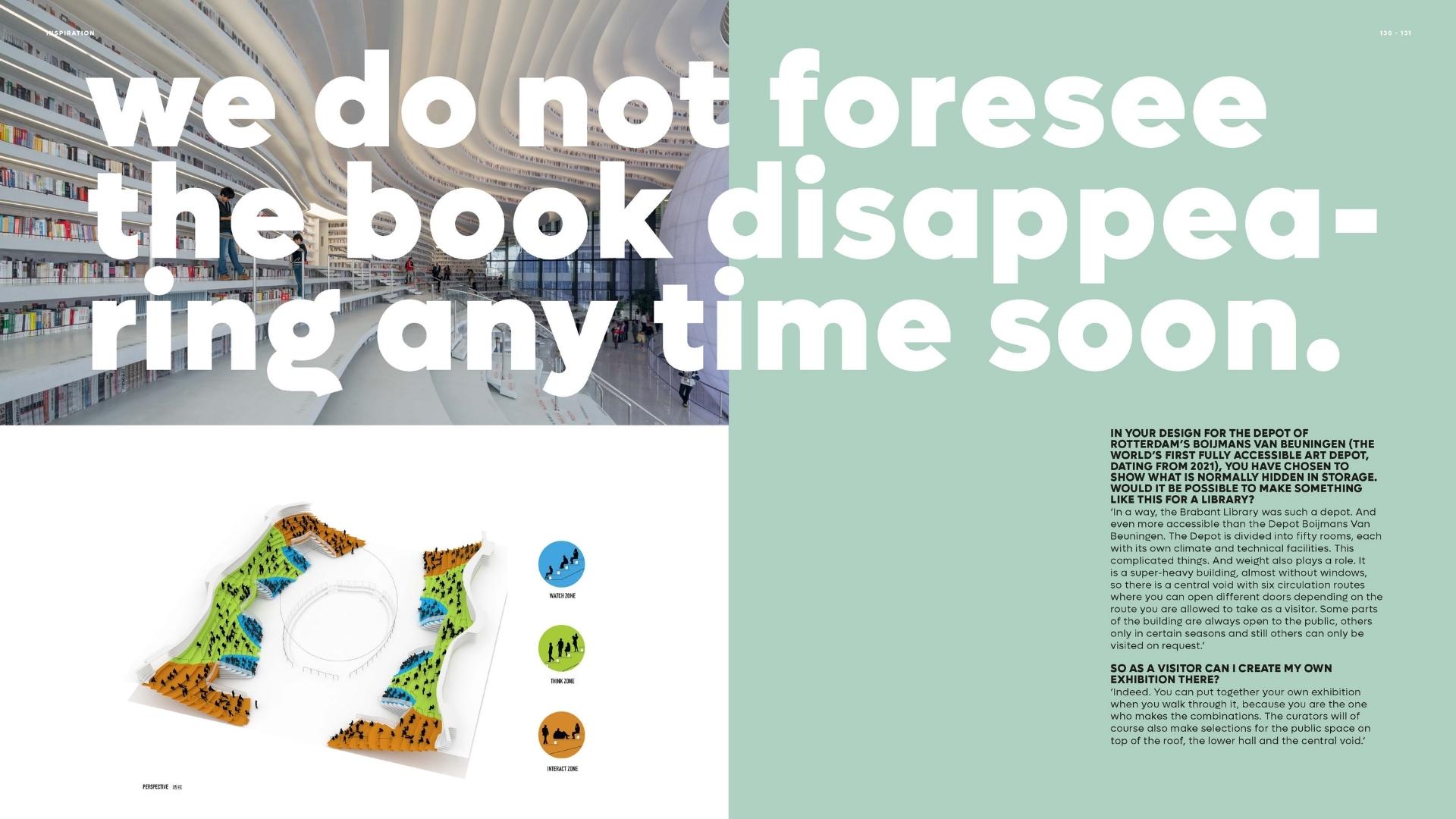

Dutch and Flemish architects are attracting attention with high-profile and innovative public library buildings. Their designs are valuable sources of information and inspiration. We spoke with them about their vision for the public library and asked them how they look back on the design process.

- Jo Coenen: OBA, Amsterdam (NL) and Centre Céramique, Maastricht (NL).

- Chris van Duijn (OMA): Seattle Central Library (US), Qatar National Library, Doha (QA) and Bibliothèque Alexis de Tocqueville, Caen (FR).

- Francine Houben (Mecanoo): Library of Birmingham (GB), Tainan Public Library (TW), New York Public Library Stephen A. Schwarzman Building (US), The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library (US), New York, Martin Luther King Library, Washington (US). – Winy Maas (MVRDV): Boekenberg Spijkenisse (NL), Tianjin-Binhai library (CN), imaginary Brabant Library 2040 (NL).

- Vincent Panhuysen (KAAN architects): Utopia, Aalst (BE).

- Michiel Riedijk (Neutelings Riedijk): Rozet Arnhem (NL) and Eemhuis Amersfoort (NL).

- Gert Kwekkeboom and Rick ten Doeschate, Civic: LocHal Tilburg (NL).

- Kamiel Klaasse and Pieter Bannenberg, NL Architects: Groninger Forum (NL).

- Ralf Coussée and Klaas Goris (Coussée Goris Huyghe architects): Waalse Krook Library Ghent (BE).

IMAGINATION: DON'T START BY REDESIGNING THE IMAGE; REDESIGN THE ACTION

The (re)construction of a library is complex, as many decisions must be made in a short period of time. Then it is important to formulate a number of starting points in advance, which give direction to the design process. We call that a “program of imagination” because it is our inspiration in making the right choices. We distinguish five main focal points in such a program:

- A new library is an investment in the future. But building for the future is only possible if we have a good understanding of the essence – the mission – of public library work.

- Public libraries are operating in a rapidly changing context that needs to be adequately addressed. It is important to map these transitions beyond the delusion of the day, the hypes or the trends: what are the essential changes in our information society?

- Changes in society and new technologies require a different way of working, with a central role for the user, a different use of the collection and new forms of collaboration. What role will collection, users, partners and programming play?

- A different way of working results in different programming, which also places new demands on the architecture and layout of the future building. What does that mean for the spatial layout and placement of the collection? What makerspaces will there be? And what can other partners add in terms of functionality?

- Experiment, because will everything work the way it was conceived? The best way to find out is to explore other ways of working in a laboratory for new library work, where concepts and ideas are tested with users.

FINALLY

Libraries are and will continue to be essential to the social and cultural vitality of a community. Under the influence of technological and social changes, the library will have to continue to innovate constantly, and this requires buildings that allow for new forms of library work. It requires an innovative architecture, where architects and librarians can learn a lot from each other and challenge each other.

The library is worth it!

Rob Bruijnzeels and Joyce Sternheim are librarians who have been working on the transition of library work for some time. In 2019, they received the oeuvre award from the Victorine van Schaick fund from the Royal Dutch Association of Information Professionals for “their unrelenting contributions in word and deed to Dutch public library work.

More background information on the book is available on the website imaginationandparticipation.com